Santa Rosa & San Jacinto Mountains National Monument

A celebration of beauty and history in

The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains

National Monument

by Ann Japenga

If you want to know these mountains, there’s no better guide than J. Smeaton Chase, an Englishman who toured the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto mountains in 1915 with his burro, Mesquit. Chase was baked senseless by the stupefying heat. His coffee cup was blown away by “the pestilent wind” ripping through the San Gorgonio Pass. He was evicted from his coyote skin sleeping bag by a flash flood down Chino Canyon.

When he ended his visit, you’d think Chase would care little what became of this uncouth land. But the thoughtful tourist wrote a book, California Desert Trails, urging that these mountains be preserved for all time as a national park.

Travelers before and after have come to a similar conclusion. No matter how many cholla spikes they flick off their socks, they still want to see this beautiful and sometimes prickly place protected.

And it finally happened.

On Oct. 24, 2000, legislation introduced by U.S. Rep. Mary Bono was signed into law, and the stomping grounds of J. Smeaton Chase and Mesquit became The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument.

Hold on, you say: Why didn’t Mr. Chase get his national park? It’s true the national monument designation sometimes confuses people. To clear up matters: A national monument is not a “junior” national park, even though some monuments, such as Joshua Tree, are eventually redesignated as national parks.

At one time in history, monuments and parks were more distinct, but these days there is no substantial difference (to the public, anyway), says Hal Rothman, professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and author of a book on national monuments. Both titles are the equivalent of an Academy Award: the highest honor bestowed on natural areas. “The designation means you have something assessed as important to the nation, not just your region,” Rothman says.

The label also means we’re determined to protect our “nationally significant biological, cultural, geological and recreational resources.” But “resources” is too paltry a word to encompass the abundance and vitality found in these mountains.

Out there is a teeming world of hidden waterfalls, rockhounds, mystics, hermits, botanists, rattlesnake researchers, nomadic artists, Indian artifacts, and more than 500 plant species, each with a personality you could spend a lifetime getting to know. Want to meet a Tahquitz ivesia or a San Jacinto prickly phlox? You’ll only find it here.

“Resources” would include the wild bighorn lamb, Ambrosia, whose life was saved atop Bradley Mountain by a sheep researcher applying mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. And Manuel Hamilton, chairman of the Ramona Band of Cahuilla Indians, who can tell you about making bone arrows and collecting healing teas as a boy up on Cahuilla Mountain, an area the Ramonas deem a sphere of influence to the national monument. Or the Wellman family, which has ranched Texas Longhorn cattle in the San Jacinto Mountains since the 1800s.

The monument and its resources are too sprawling and big (272,000 acres) ever to be contained in a management plan—but still it’s someone’s job to try. That someone, the first manager of the monument, is Danella George. Blonde and irrepressible, George grew up a California surfer girl and still looks and acts the part. Her management style is friendly and surfer-casual.

George has happy memories of visiting the desert as a child: chasing lizards with her friend Smitty and diving into the El Mirador Hotel pool, where you could hold your breath and wave at your parents in the subterranean bar.

Returning to the desert as an adult, George was riveted by the escarpment. “The mountains here are so straight up and open,” she beams. “Much of the history and ecology for the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto mountains can be attributed to their angle of repose.” George admires the slope mostly in passing these days as she sprints from meeting to meeting.

The endless meetings are necessary to coordinate the hundreds of people involved in the monument venture. There’s a convergence of electricity and creativity around the new monument right now. As George says: “It’s intensely cooperative and evolving.”

It’s been a cooperative effort right from the earliest days. Over the decades, many influential folks have championed preserving the mountains as a national park or monument. Among the advocates: Desert Magazine founder Randall Henderson, author John C. Van Dyke, first Palm Springs Mayor Philip Boyd, and Desert Center founder Steve Ragsdale.

Other distinguished outdoorsmen added their vote simply by visiting and expounding on what they saw: Edmund Jaeger, famed botanist and an authority on deserts worldwide; Ansel Adams, the country’s premier landscape photographer; and John Muir, America’s greatest conservationist.

Like Chase, John Muir was socked by the desert heat, which brought to mind for him “Milton’s unlucky angels.” But like Chase, he found ample consolation. “O the beauty of the sky evening and morning,” he wrote to a friend.

In recent years, a band of tireless boosters again revived the crusade for federal protection. Names that come up again and again are Bill Havert, executive director of the Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy; Buford Crites, Palm Desert Councilman; Joan Taylor of the Sierra Club; Corky Larson, former Coachella Valley Association of Governments executive director; Katie Barrows, associate director of the Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy; Ed Hasty, former Bureau of Land Management state director; and Ed Kibbey, executive director of the Building Industry Association’s Desert Chapter.

The advocates received the help of Congresswoman Mary Bono, as well as U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who introduced a companion bill in the Senate. “You have to give final credit to Mary Bono,” says Havert. “She did what was necessary to finally make this happen.”

Of course, since this is Palm Springs, we couldn’t do a national monument the way everyone else does it. We had to innovate. This would be the first national monument created through a cooperative effort of Congress rather than a presidential dictate. What this means is the monument has broad support. Unlike some hastily decreed monuments, it’s not going away.

In another departure from convention, the entire Palm Springs Valley building industry backed the monument. “Normally when you talk about declaring something a national monument, the building industry would have apoplexy,” says Crites. “But here we had Ed Kibbey of the building industry, and Joan Taylor of the Sierra Club sitting down together and saying, ‘How are we going to fix this so we have something we can all love and live with?’”

More innovation: The management plan is an experiment in radical cooperation, with the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service sharing the reins equally with the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. State agencies, local governments, several Indian tribes and a host of partners all weigh in on decisions.

Guiding the monument for the San Bernardino National Forest is San Jacinto District Ranger Laurie Rosenthal. She acknowledges the old monolithic way of doing business might be easier, but she believes the fruits of cooperation and community involvement make it worth the added effort.

“We may be the managers of this monument, but this is not our land,” Rosenthal says. “It’s everybody’s land. We really want this to be a community-supported monument.” That means the public will be involved in everything from monitoring archeological and biological sites to maintaining trails and educating schoolchildren about the monument’s nine threatened and endangered species, including the southern yellow bat and the least Bell’s vireo.

A final first is the inclusion of an Indian tribe as an equal partner in the monument. In the 1920s, the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians nixed several attempts to include the Indian Canyons in a proposed national park — without the tribe’s input.

Today the tribe has equal say. “For the tribe, monument status means we are now able to work with other agencies in protecting cultural sites off the reservation,” says Barbara Gonzales Lyons, vice chairman of the Agua Caliente Tribal Council. “We want to do the gamut of protection — the native plants, trails and water resources as well.

“This is where my people began,” she adds. “This is where we’ve always been.”

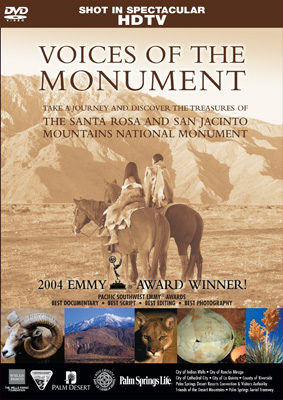

Voices Of The Monument

Take a journey and discover one of North America’s most unique and diverse mountain ranges. Learn about the native Cahuilla Indian Tribes and how they survived in such extreme environments. Soar over some of the most spectacular geological landscapes from indigenous palm oasis to one of the largest rockslides in the world. View spectacular footage of the endangered and illusive Peninsular Big Horn Sheep; plus a range of animal, bird and plant life encompassing five different life zones. Shot in spectacular high definition HDTV you'll experience the detail of this diverse and seldom seen land.

2004 PACIFIC SOUTHWEST EMMY® AWARDS -

BEST DOCUMENTARY • BEST SCRIPT • BEST EDITING • BEST PHOTOGRAPHY

Proceeds from the sale of this Emmy® Award winning documentary will go to the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument.

Preview a short clip of the DVD